05/27/1927 • 13 views

1927 Diphtheria Antitoxin Tragedy: Early Mass Poisonings Tied to Contaminated Alcohol

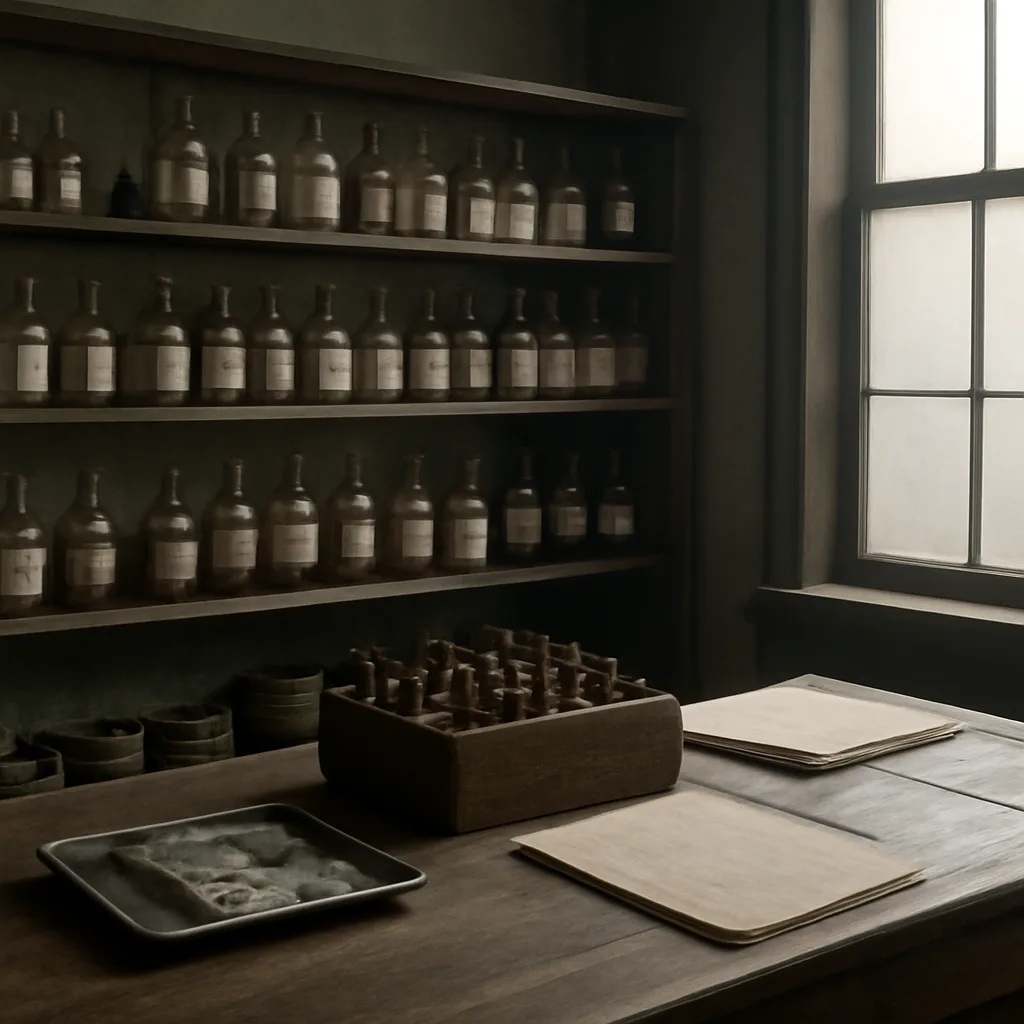

In late May 1927, a batch of diphtheria antitoxin contaminated with wood alcohol (methanol) caused widespread poisoning among recipients — an early documented mass toxicological event linked to alcohol contamination in medical supplies.