04/28 • 17 views

First U.S. Consumer Product Recall Traced to 1932 Poisonings

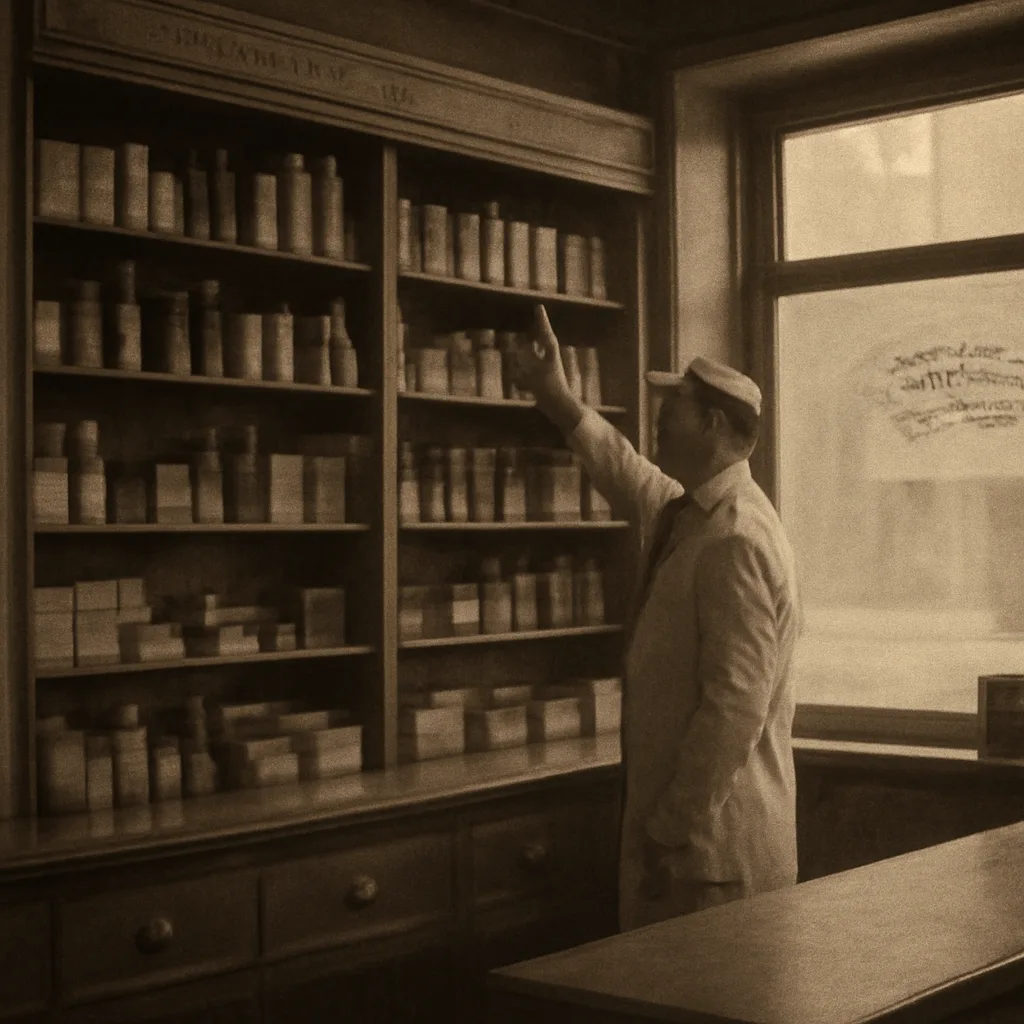

On April 28 (year disputed), investigations into acute poisonings linked to a widely sold patent medicine prompted what newspapers and public-health historians describe as the first documented U.S. consumer product recall, highlighting early tensions between commerce and public safety.