03/17/1901 • 23 views

March 17, 1901: First documented mass deaths linked to a patent medicine

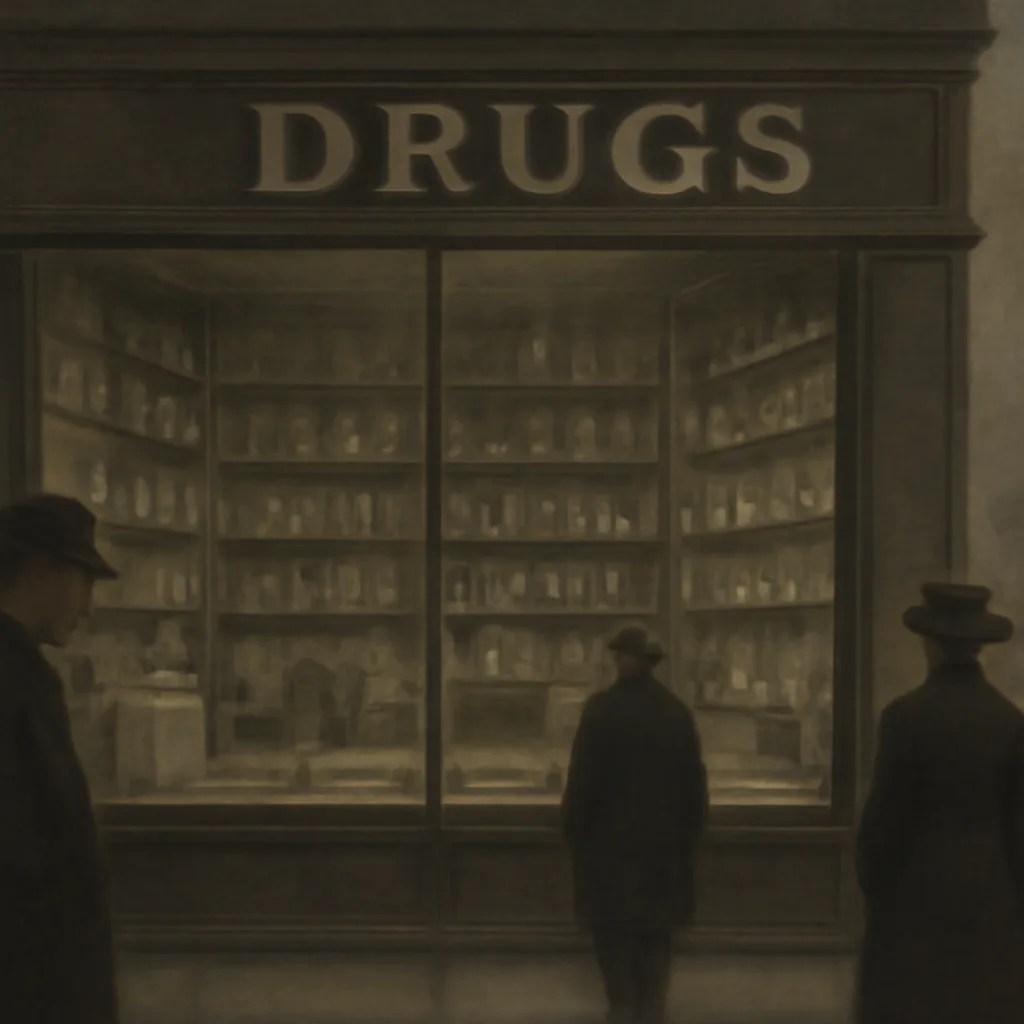

On March 17, 1901, a single incident tied to a commercial patent medicine led to multiple fatalities, prompting early public alarm about unregulated remedies and fueling calls for oversight of ingredients and labeling.