03/13/1971 • 22 views

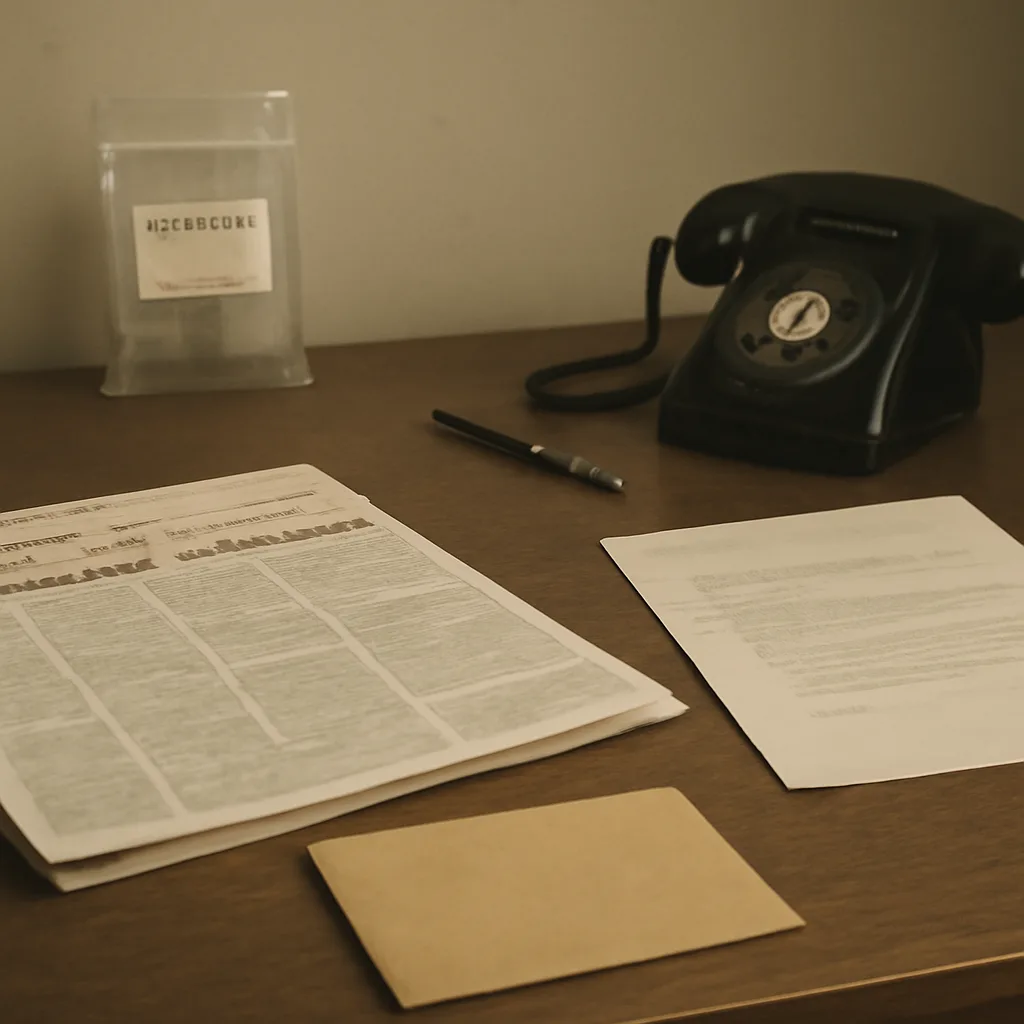

Zodiac Killer Claims Another Victim in March 13, 1971 Letter

On March 13, 1971, a letter received by a Northern California newspaper claimed the Zodiac Killer had murdered another person; the correspondence renewed debate about the case’s timeline and the letter’s authenticity.