05/03 • 14 views

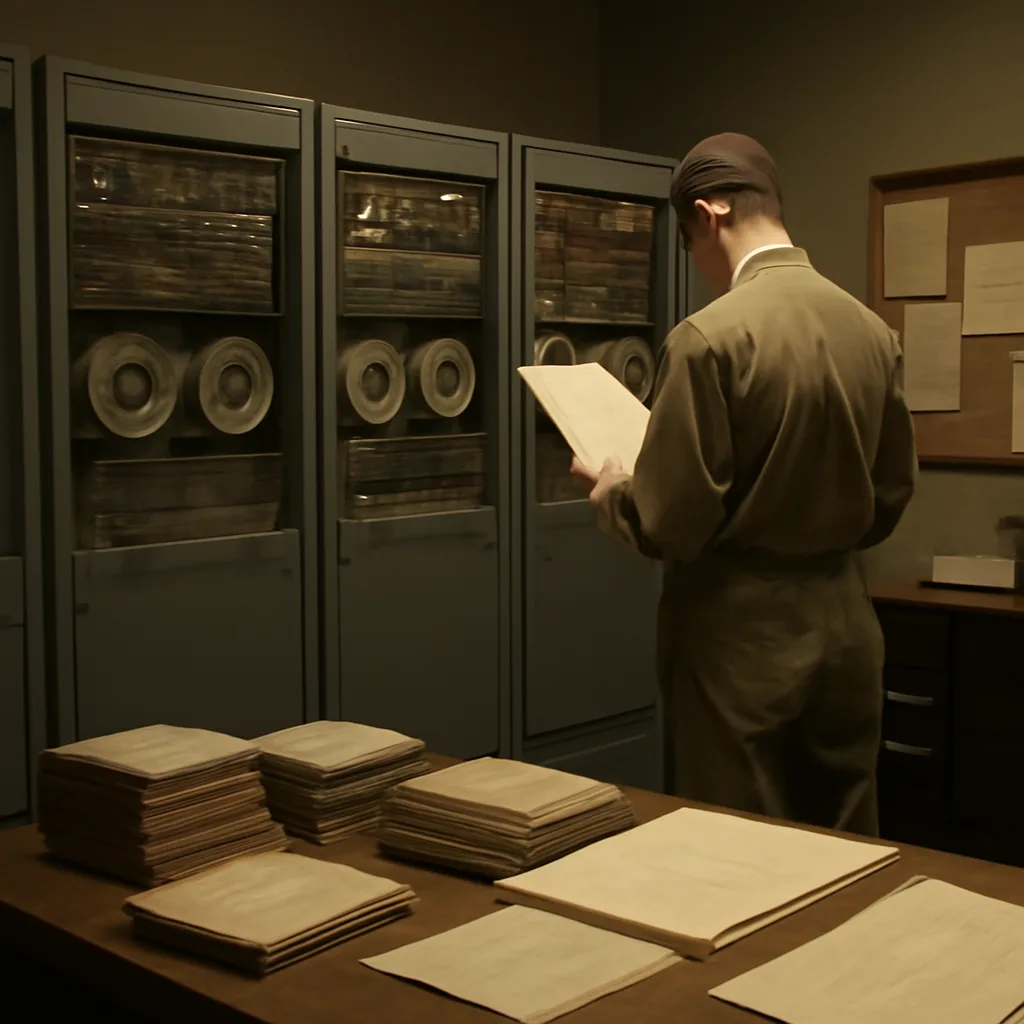

Early concept of a self-replicating computer program outlined

On May 3 (year uncertain), a pioneering description of a program capable of producing copies of itself was circulated, marking an early articulation of self-replication in computation that influenced later work on viruses and automata.